A whirlwind introduction to the challenges of recording native code and how to overcome them.

Introduction

Like any good idea in computer science, record & replay debugging dates back to the 1960s. Robert Balzer's Extendable Debugging and Monitoring System (EXDAMS) is quoted as the earliest system to implement the idea. EXDAMS worked by capturing dynamic events like function calls, branches, and variable assignments to a history tape. Replay could then restore any program state by applying the deltas from the tape.

Nowadays, with millions of function calls and billions of variable assignments per second, such an approach would clearly be infeasible. That's why modern implementations are based on one key insight: Computers are (mostly) deterministic. If you save which program you executed and what inputs you passed to it, it will (mostly) perform the same function calls and variable assignments again if you rerun it with the same inputs. In this setup, any program state can be recreated by rerunning the program from the start and stopping at the desired point in the execution. Variable values and other source level information can be extracted from the assembly level machine state using debug info like in a regular step debugger.

The only problem is that computers are not actually deterministic. There are all kinds of sources of non-determinism in a modern system. They range from more obvious examples like time() and os.random() to more subtle things like address space layout randomization (ASLR) and race conditions. Trying to address each of these issues individually would lead absolutely nowhere, as there are just too many of them. Instead, we will use a bottom-up approach and analyze sources of non-determinism in user space programs from first principles.

Let there be Registers

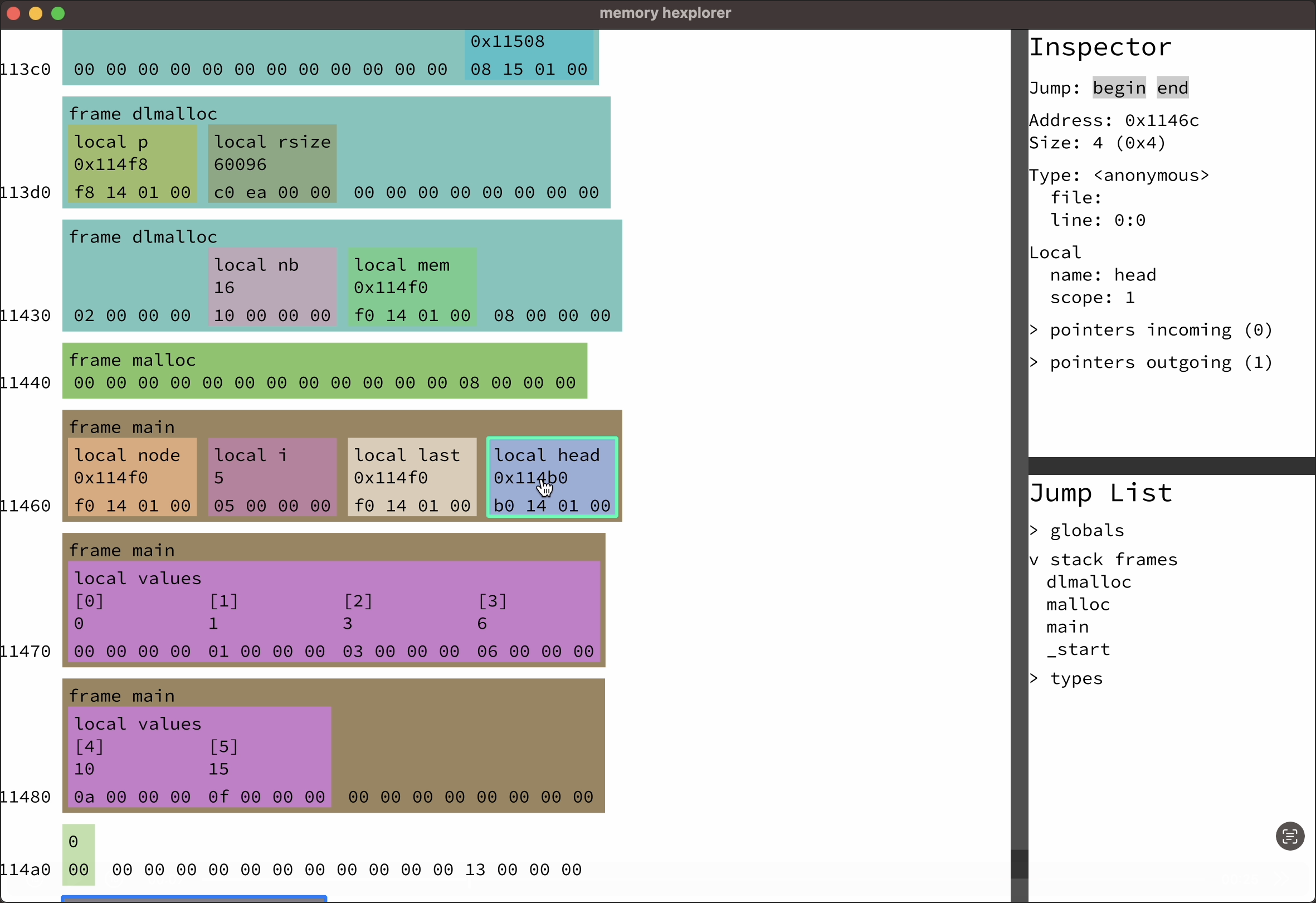

The most fundamental piece of state in any program are the cpu registers. There is only a limited number of them, and they have fixed sizes, so they are very easy to reason about. On AArch64, we can represent them like this:

struct AArch64State { pc: u64, x: [u64; 31], sp: u64, cpsr: u32, v: [u128; 32], fpsr: u32, fpcr: u32, }

If we want to be able to replay any program, we will have to know what its initial register values were when we recorded it. The most simple and robust way to do that is to simply write all their values to the recording file before executing any code.

Let there be Memory

The natural next step would be to talk about the program code and simple instructions like add. But since the program code lives in memory, we have to talk about that first. Thanks, Mr. von Neumann.

Like the registers, memory is a finite resource. Conceptually, it is an array of 2^64 bytes with unknown initial values. A mathematician may therefore recommend simply writing their values to the recording file before executing, like we did with the registers. Not only is this a joke, but it would also be entirely unnecessary, as modern systems use "virtual memory". This means that only parts of the 64 bit address space are actually "mapped" to physical memory. The rest is inaccessible and results in a hardware exception when accessed. So what we can do instead is ask the operating system which parts of our address space are mapped, and only capture the contents of those accessible pages. Surely that's a perfectly reasonable approach, right? Right?

Sharing is Caring

On Linux, yes, walking the virtual memory mappings at startup and capturing their page contents is perfectly reasonable. And as far as I know, that's exactly what the rr time travel debugger does. It works just fine because on Linux, a fresh process has a fairly minimal set of mappings:

- Main executable and dynamic linker: These are simple file mappings, so they can be captured by cloning the underlying files, which is essentially free.

- Main thread's stack: Contains program arguments and environment variables, which need to be captured, the rest is zeroed.

- Initial heap/brk area: Zeroed, only size needs to be recorded.

- Some special kernel memory regions: Presumably ignored by

rr, we'll talk more about one of these mappings later.

But macOS thinks different. On top of the mappings listed above, it has an additional 4.5 GiB mapping known as the "shared cache". It is a collection of system libraries that includes libc, the Objective-C runtime, CoreFoundation, and many others. And while the shared cache is also backed by a file on disk (several actually), we can't just clone those files and call it a day.

That's because the shared cache uses a custom pager that loads the shared cache pages on demand and applies relocations to the functions within them. You don't have to know what that means, just that there are currently 5 different relocation formats, and that we don't really want to replicate all that logic. But just capturing the entire shared cache by copying the pages doesn't work either, as that would make every recording 4.5 GiB before any code has even executed. So what can we do instead?

Fine, I'll be the OS

To recap, we have this giant 4.5 GiB mapping in our process with unknown contents. It's hard to replicate and it's too large to copy unconditionally. But this actually isn't the only time we run into this problem. It also happens when the program uses mmap to map a large file into memory. In that case, one approach would be to clone the underlying file, like rr does. But back when I wrote my first recorder, I didn't know that was an option on macOS. So I came up with a different idea.

When a program maps a large file, the OS actually faces a similar problem: mmap is supposed to return quickly, regardless of how large the file is. But at the same time, the program is supposed to be able to access any byte in the memory mapping and see the file contents. This dilemma is resolved by reading pages from disk ad-hoc when they are first accessed. The OS does this by mostly just recording some metadata when you call mmap. The pages remain inaccessible at hardware level, so when the program accesses one of them, it raises an exception. The OS then handles that, realizes the faulting page has a file mapping, reads the page contents from disk, inserts the page into the page table, and resumes program execution as if nothing had happened.

My (old) approach to the shared cache problem was inspired by that idea: I artificially reduced the access permissions of unknown memory regions to PROT_NONE. Which meant that if the program accessed them, it would trigger a fault and raise a signal in the user process. I then caught that with my recorder runtime's signal handler, restored the original permissions of the page (eg to PROT_READ), and saved the page contents to a "page captures" file before returning from the signal handler as if nothing had happened. This worked surprisingly well, but it definitely wasn't a cheap solution. Baseline signal delivery overhead is around 2.3 µs on my machine, which is before calling mprotect and copying page contents. But my old recorder never got fast enough for that to become a bottleneck.

Sharing really is Caring

This leads us to the next issue: shared memory. Shared memory usually refers to memory that is shared between different processes. But for the purposes of deterministic record & replay, we can also consider the memory within a process to be shared by the threads of that process. Both kinds of shared memory break determinism when there is parallel execution. That is, when multiple cpu cores execute code at the same time. Because on modern hardware, cpu cores can dynamically adjust their frequency, so on some runs of a program, one thread may be faster to acquire a lock, and other times it could be a different thread (or process, in the inter-process scenario).

So when code executes in parallel and shares memory, we lose determinism. But we can't really stop programs from sharing memory, because that would severely limit the number of programs we can run. We can, however, prevent them from executing in parallel! Of course, this can be extremely expensive for highly parallel code. But let's be real, most code barely even manages to fully utilize the single thread it's running on. Hence the "let's just not execute things in parallel" approach is actually feasible and is exactly what rr does in practice. But not all record & replay systems use this approach. WinDbg and my own recorder allow both parallel execution and shared memory, though that does come at a cost, and we'll talk about it in a later section of this article.

Control Issues

For now, we have another problem, because we can't always control all processes participating in a shared memory mapping. A program may open a shared memory file that's also accessed by a process outside of the recording process tree, or it may communicate with some OS driver via shared mappings. In such cases, we cannot prevent parallel accesses. And believe it or not, rr simply does not support this case. On their website, they mention that they disable the shared memory extension of the X11 window system for exactly this reason.

But another time travel debugger, Undo.io, does support sharing memory with external processes, even though they also use the "single core execution" trick for determinism within their recording processes. I haven't found much public information about how they do it other than this quote from their comparison with rr: "Using a clever combination of instrumentation and the MMU on the host system, Undo can retranslate blocks of code that access shared-memory and store their non-determinism in the event log."

My guess is that they remove read permissions from pages that are shared with other processes. When a thread accesses such a page, it will fault, just like with my "lazy page capture" idea from earlier. One option would be to record the value that was read when this happens and continue execution. But like I mentioned, the overhead for this is on the order of microseconds, so that's not a great idea. It sounds like what they do instead is that they rewrite the machine code to insert logging code into it. They presumably create a secondary mapping of the shared memory elsewhere in the virtual address space with the regular access permissions, which the rewritten machine code then accesses. But that's just a theory, a game theory!

Time Sharing

Native code really likes to share memory. We've talked about sharing memory between threads, recorded processes, external processes, and drivers. What's missing from that list? Exactly, the OS kernel itself.

macOS has a mapping known as the Commpage, and Linux has the VVAR region. These mappings are most well known for being used to accelerate the gettimeofday system call. Instead of making a real system call, which is considered to be fairly expensive, libc implementations can read the current time from those shared mappings, which are updated by the kernel in the background.

Now, I don't know the details of how that works, but it sounds pretty expensive to me. Given that the baseline latency for syscalls is around 100 ns on my machine, the kernel would have to update that value pretty often for it to be "better than a syscall" if we assume that we want an accurate value. But it does look like this mechanism is still used on modern macOS. And the value seems to be updated whenever someone requests the time via a syscall. I'm not sure what happens when that hasn't happened in a while though.

In any case, the issue with the Commpage on macOS is that you can't change its access permissions. Which means that we can't use any virtual memory tricks to detect when code reads from it. The way I dealt with that in my old recorder was that I added a check to every memory access to see if it accessed the Commpage, and if so, I recorded the value. According to rr's technical report, they deal with the VVAR region on Linux by patching the vDSO (the library that accesses the VVAR region), so it always uses the fallback syscalls.

Syscalls

As we've seen, memory is complicated. Just determining its initial state and dealing with parallel accesses and kernel mappings already creates a plethora of engineering challenges. But perhaps the most obvious way in which memory is mutated non-deterministically is through system calls.

Whether you read a file, accept a network connection, or ask for resource usage with getrusage, a large number of system calls write directly to user memory. In order to replay the program reliably, all of these writes need to be captured and saved to a recording file. Unfortunately, syscalls don't follow any predictable convention for how they write to memory. This means time travel debuggers need a ton of custom logic, handwritten for every system call, in order to record them properly.

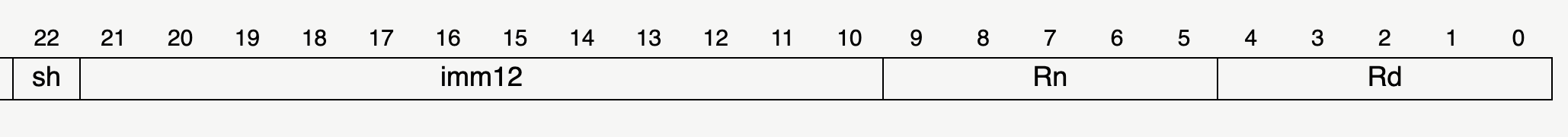

System calls also write to cpu registers, but that thankfully is predictable. On macOS/AArch64, there are two conventions. One writes only to x0. The other writes to x0, sometimes x1, and indicates syscall failure through the carry flag.

There isn't really much more to say about syscalls, it's just a lot of "boilerplate".

To Translate or Not to Translate

We just talked about capturing syscall memory writes with "a ton of custom logic". But how exactly do you run that logic when a syscall is executed? Generally, there are two approaches to this problem.

The first strategy is to use ptrace, which is what rr does. ptrace is part of Linux's debugging facilities. It allows one process to attach to another one and be notified about certain events like system calls. It can then read the other process's registers and memory, just like a regular debugger would.

The only problem with this approach is that the context switches between the recorded process and the supervisor on every syscall are very slow. That's why, in rr, it's only the fallback strategy. The main strategy is to inject a preload library that implements in-process syscall tracing. However, just injecting that library doesn't magically make the syscall instructions call the library functions. Instead, the first time a syscall instruction executes, it goes through the fallback ptrace path, where rr then tries to replace the syscall instruction in the recorded process with a call into the preload library.

So rr's approach is to mostly execute the program without modifications, only replacing instructions where ptrace overhead would be too expensive otherwise. It is possible that rr also does this for non-deterministic system register reads like rdtsc, but that's pure speculation (and according to Gippity, it does not).

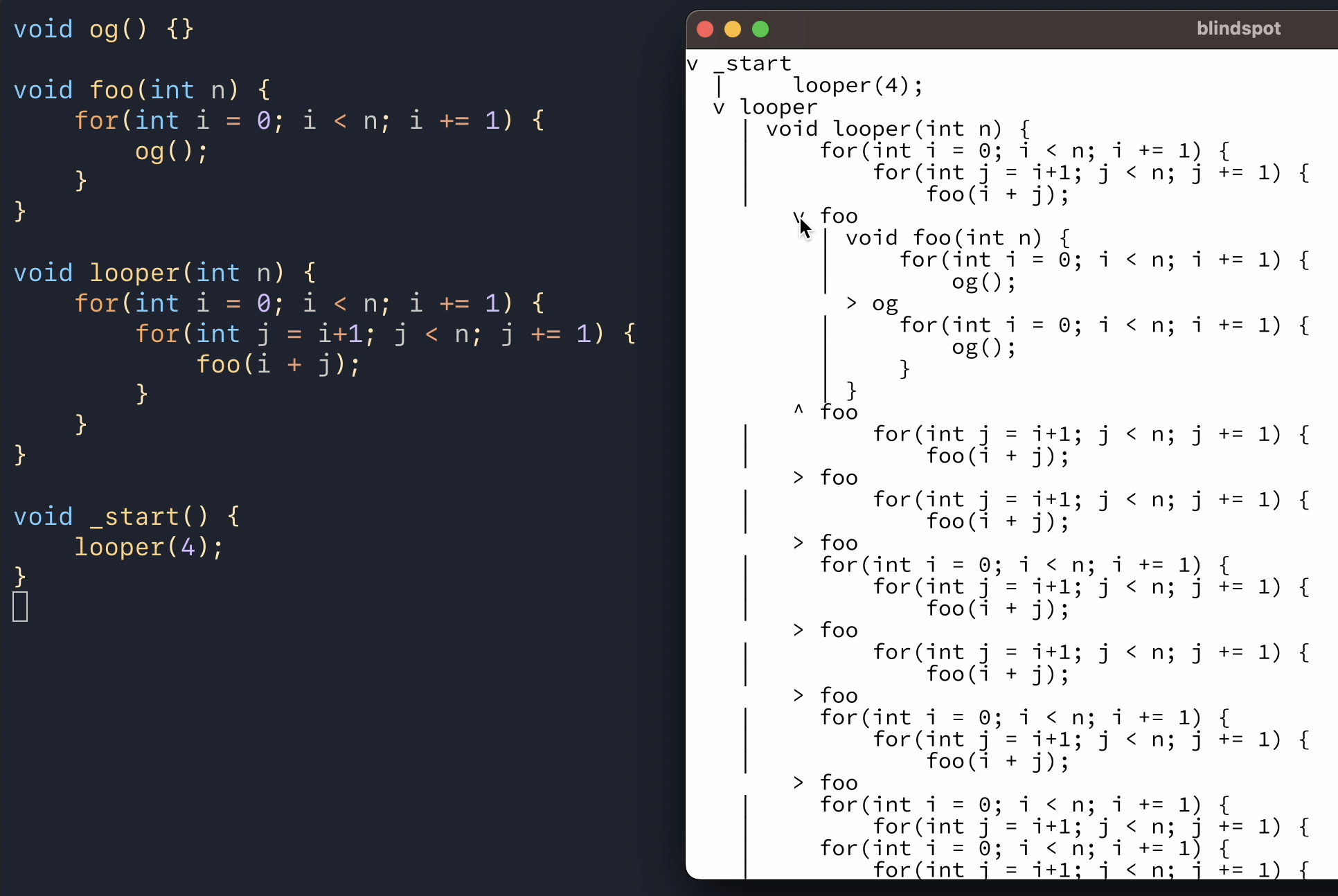

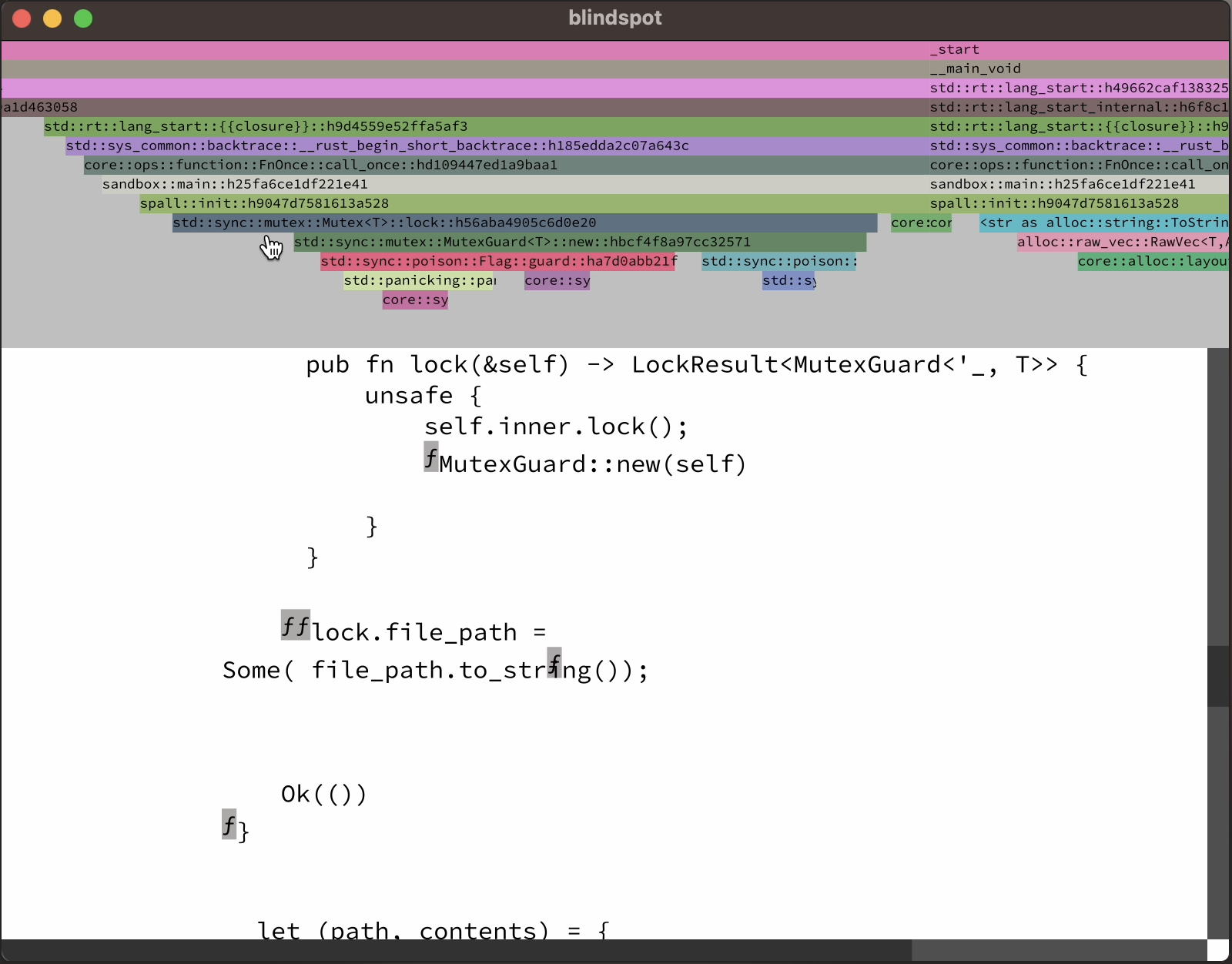

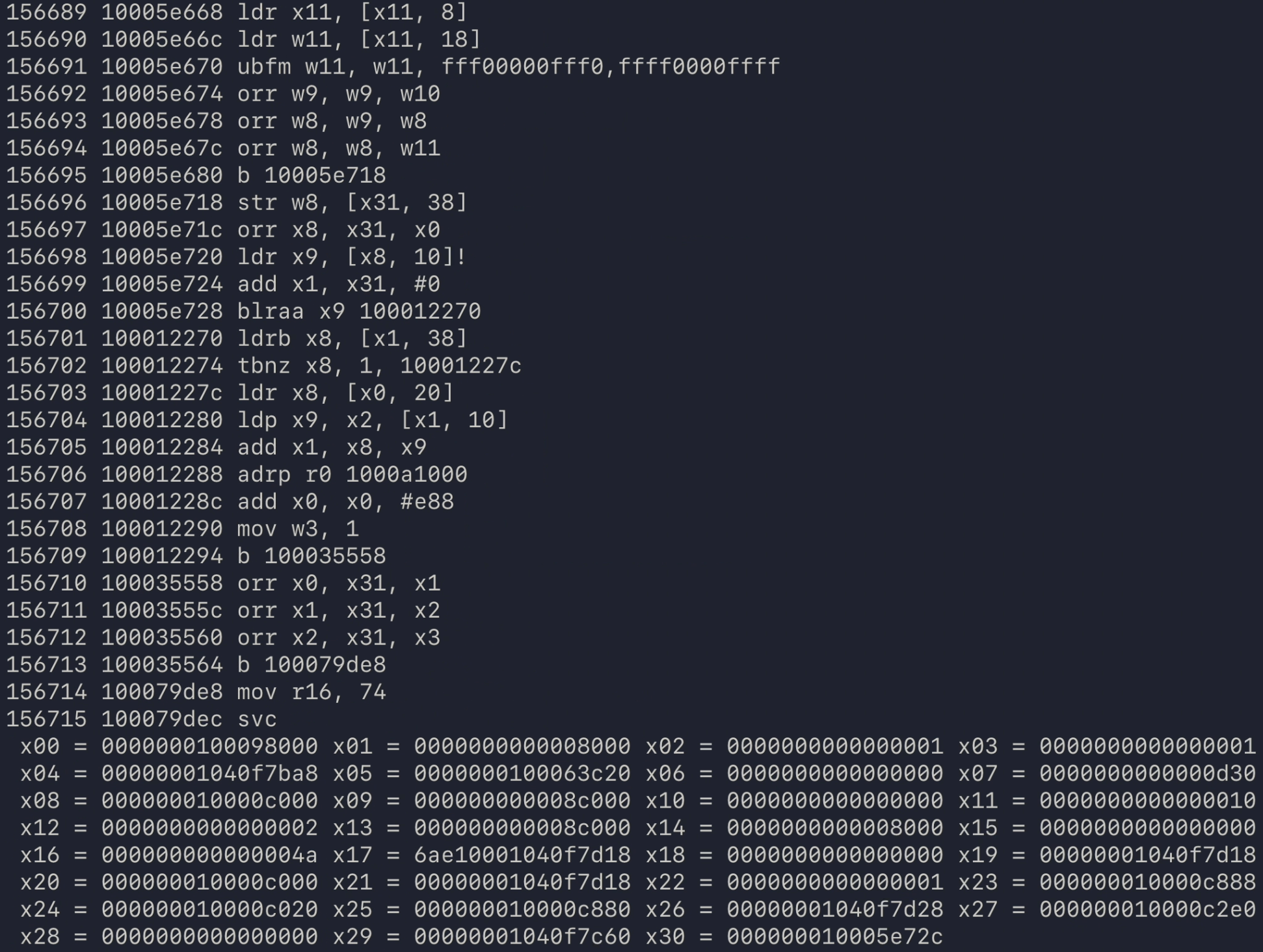

All other native time travel debuggers I know about, including Undo.io, WinDbg, and my own debugger, use pretty much the opposite strategy: rewrite everything! Also known as dynamic binary translation (DBT). The idea is that instead of executing the code in the recorded process directly on the cpu, we either interpret it or rewrite it using a jit compiler. This allows us to inject arbitrary logic anywhere we please.

One advantage of DBT is that we never have to context switch to another process for capturing non-determinism. This means heavy use of instructions like rdtsc or rdrand doesn't slow the program down nearly as much as it would in rr.

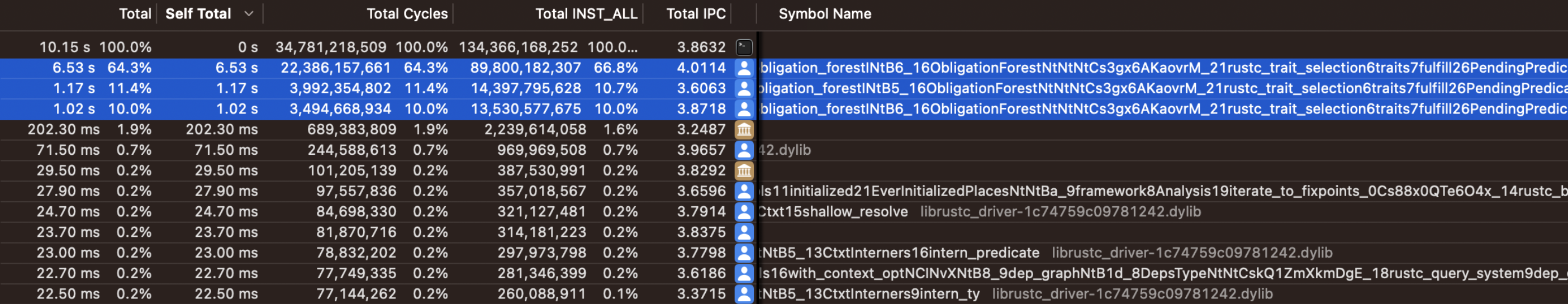

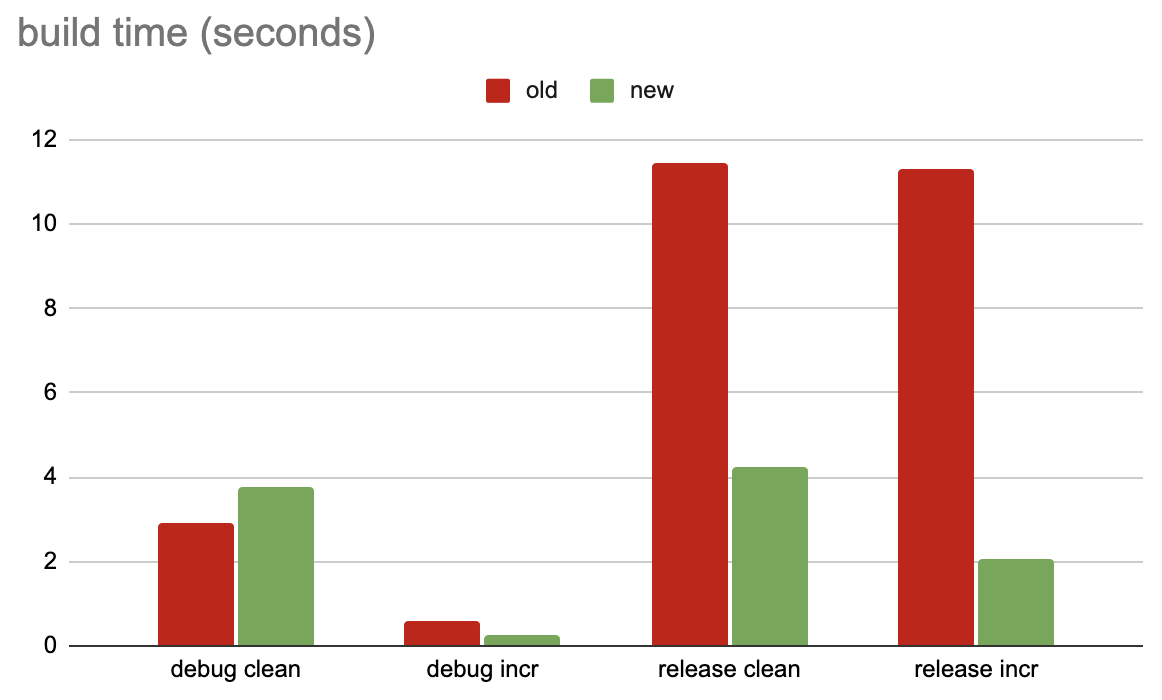

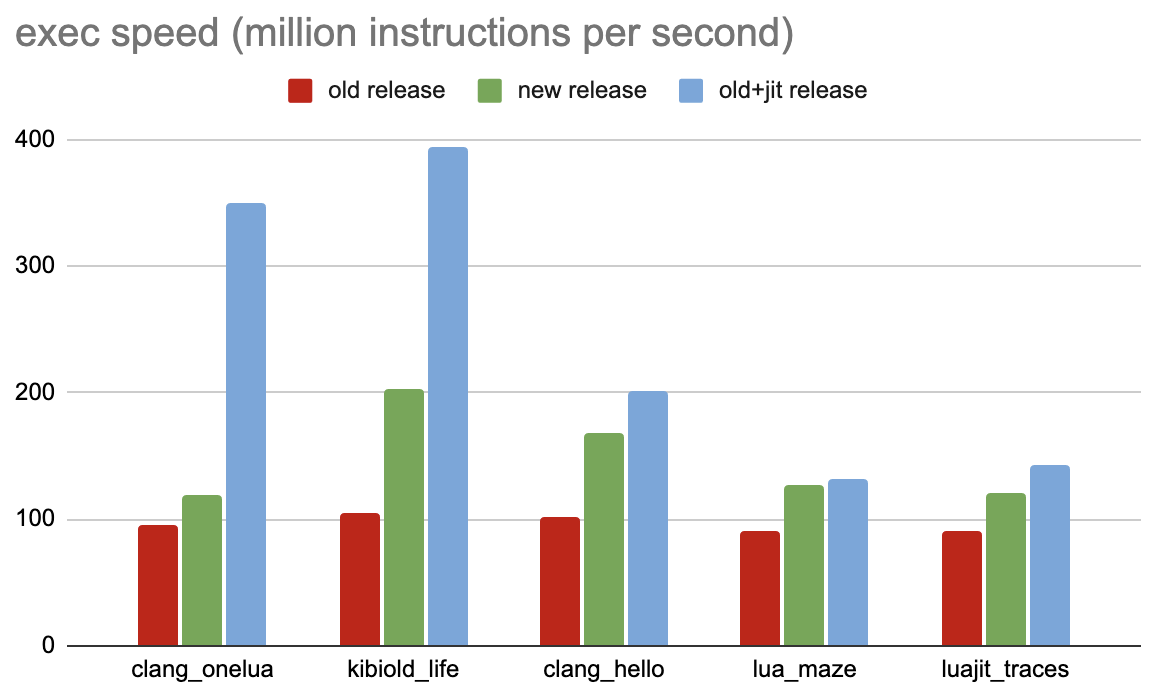

But a major downside of DBT is the translation overhead. This is especially bad for programs with lots of short lived processes like the Rust compiler. My own DBT engine saw a 12x slowdown on a Rust build without doing any recording, just translation. Most of that overhead was due to 40% of basic blocks being executed only once. I'm hoping to reduce this overhead by using my interpreter as a stage zero.

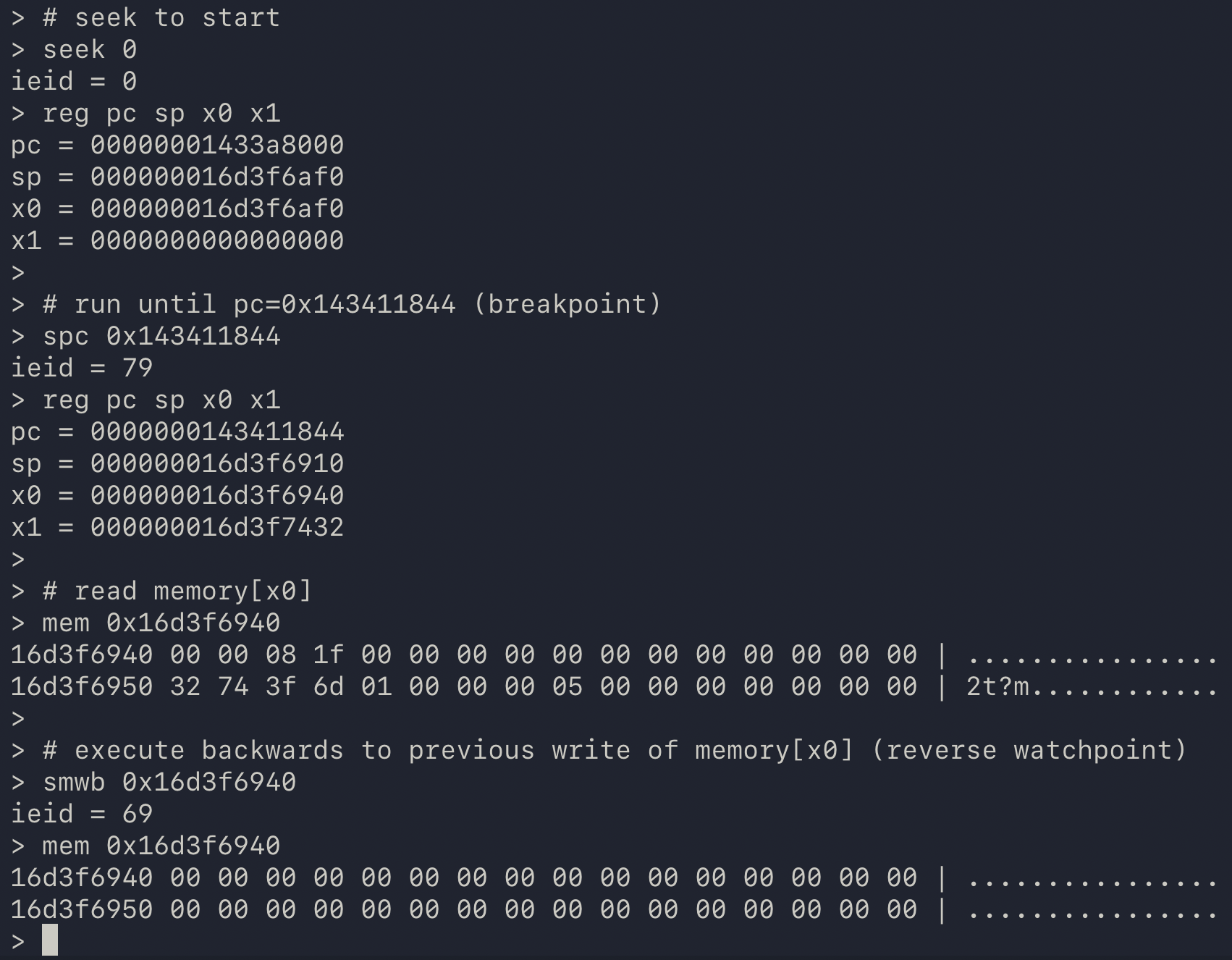

Load Tracing

And this brings us to an interesting recording strategy based on DBT that I learned about from WinDbg. Remember all the issues we had with memory and syscalls? Wouldn't it be nice if we just didn't have to deal with any of those?

Here's the idea: What if we treated memory like a black box? For all we know, it could be completely non-deterministic. The only things we know for certain are the initial register values and what code we executed. Under those assumptions, we wouldn't have to worry about parallel accesses or syscall memory writes, because we made no assumptions about the contents of memory anyway. If that was our setup, what's the best we could do?

Or, put another way, what determinism is left when we treat memory as volatile? Well, any deterministic instructions that only access register values will still be deterministic. This includes arithmetic, branches, and even stores. However, every single load becomes a potential source of non-determinism, as it pulls some unknown value from memory into a register. Which means that under this setup, we theoretically have to record the value of every single load.

But of course, recording billions of loads per second is a non-starter. Even if we just recorded a single byte for each load, we would still be recording several gigabytes worth of data every single second (especially in cpu intensive, multi-threaded applications).

So the key to making load tracing work is to not record every single load. And this can be achieved using a cache:

fn execute_load_64(address: usize) -> u64 { let value = (address as *const u64).read(); let cached = cache.read_64(address); if value != cached { record_load(address, value); cache.write_64(address, value); } return value; } fn execute_store_64(address: usize, value: u64) { (address as *mut u64).write(value); cache.write_64(address, value); }

One way to think about this cache is that it's kind of like a cpu cache, if different cpu cores didn't synchronize their caches.

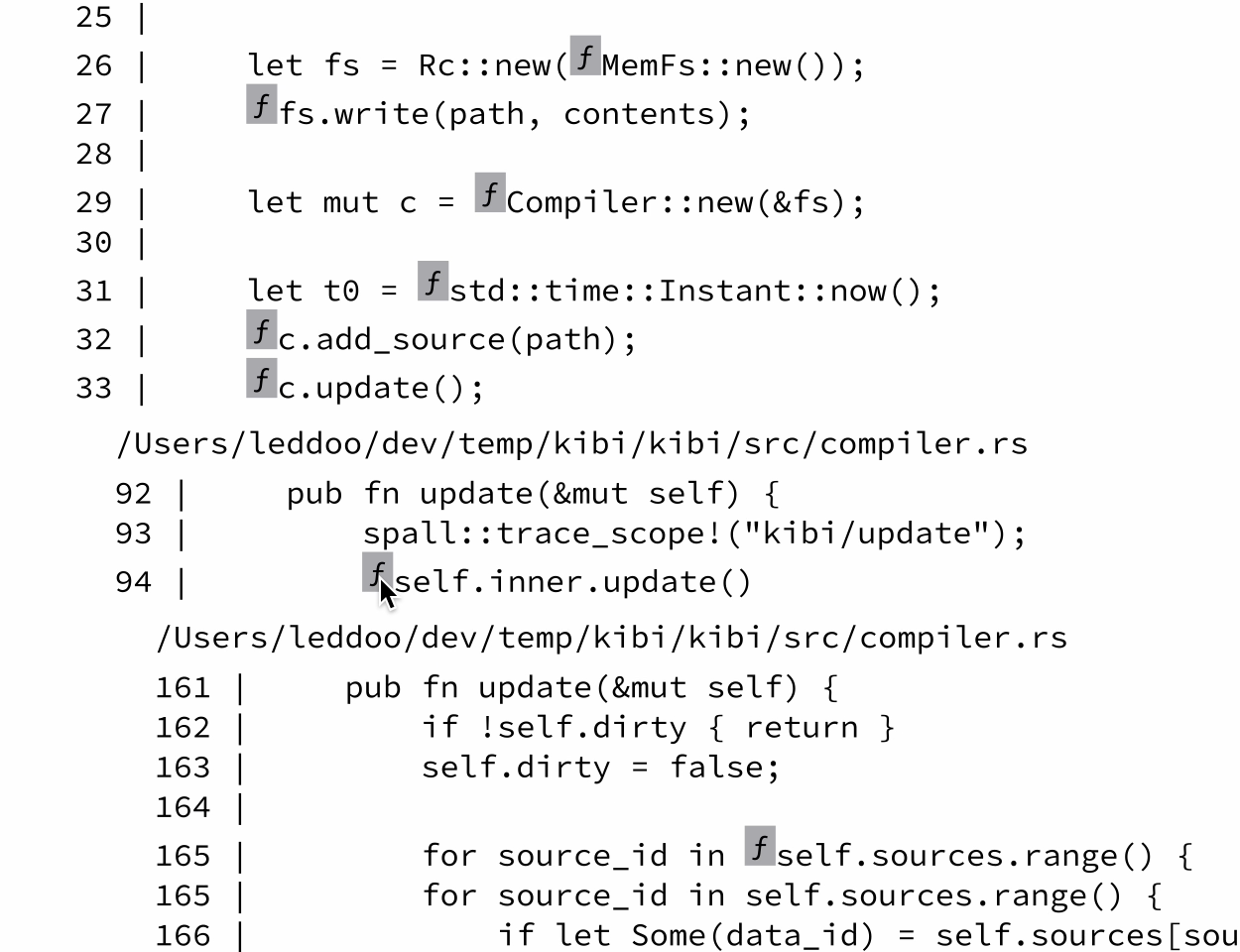

But yeah, that's the idea behind load tracing! We maintain a little cache that represents what we've observed memory to look like. And whenever we make a new observation (a load) that contradicts our cache, we record that. There is a bit more to it though. If you're curious, you can check out the iDNA paper.

In my own recorder, which also uses load tracing, I've observed cache hit rates of up to 99.85% with a data emission rate of just 40 MB/s. But that's more of a best case scenario. There are also cases where it emits over 1 GB/s. The average lies somewhere around 200-300 MB/s, which is not great compared to rr.

And doing all of this cache maintenance definitely isn't cheap either. WinDbg's docs mention a "10x-20x performance hit in typical recording scenarios". However, I've observed 30x-100x on the workloads I've tested. My own recorder does a little better at around 5x-6x on average, but for performance sensitive code like games, that would still be a deal breaker.

Given those, um, less than flattering performance metrics, you may rightfully ask why I went with load tracing. One benefit is definitely that it allows for parallel execution. Even with the 6x overhead, highly parallel code would be faster under my recorder than under rr when executing on a machine with more than 6 cores, which is most dev machines nowadays.

But the real reason for choosing load tracing is its robustness. I don't have to fully understand every single syscall, and I don't have to carefully babysit memory to make sure there are no mutable mappings shared with external processes. As a solo developer, these are serious time savers. Especially on macOS, where the operating system is littered with all kinds of performance optimizations that can easily introduce non-determinism if you're not careful. I assume Microsoft chose load tracing for WinDbg for similar reasons.

Conclusion

I hope you enjoyed this introduction to recording native code! If you did, consider joining the project's discord to be notified about future blog posts. It's a little quiet there at the moment, but I'm sure we'll have lots to talk about once we hit alpha. Which is gonna be a hot minute though, so no rush :P

Alright, that's it!